A recent post by Gregory Sadler inspired me to track down the passage above. Prof Sadler's post outlines the issues surrounding a decontextualised quote in reasonable depth, so what I want to do here is focus on what Epictetus is likely to have meant if we take this passage as being accurate.

Enduring (Bearing) and Renouncing (forbearing)

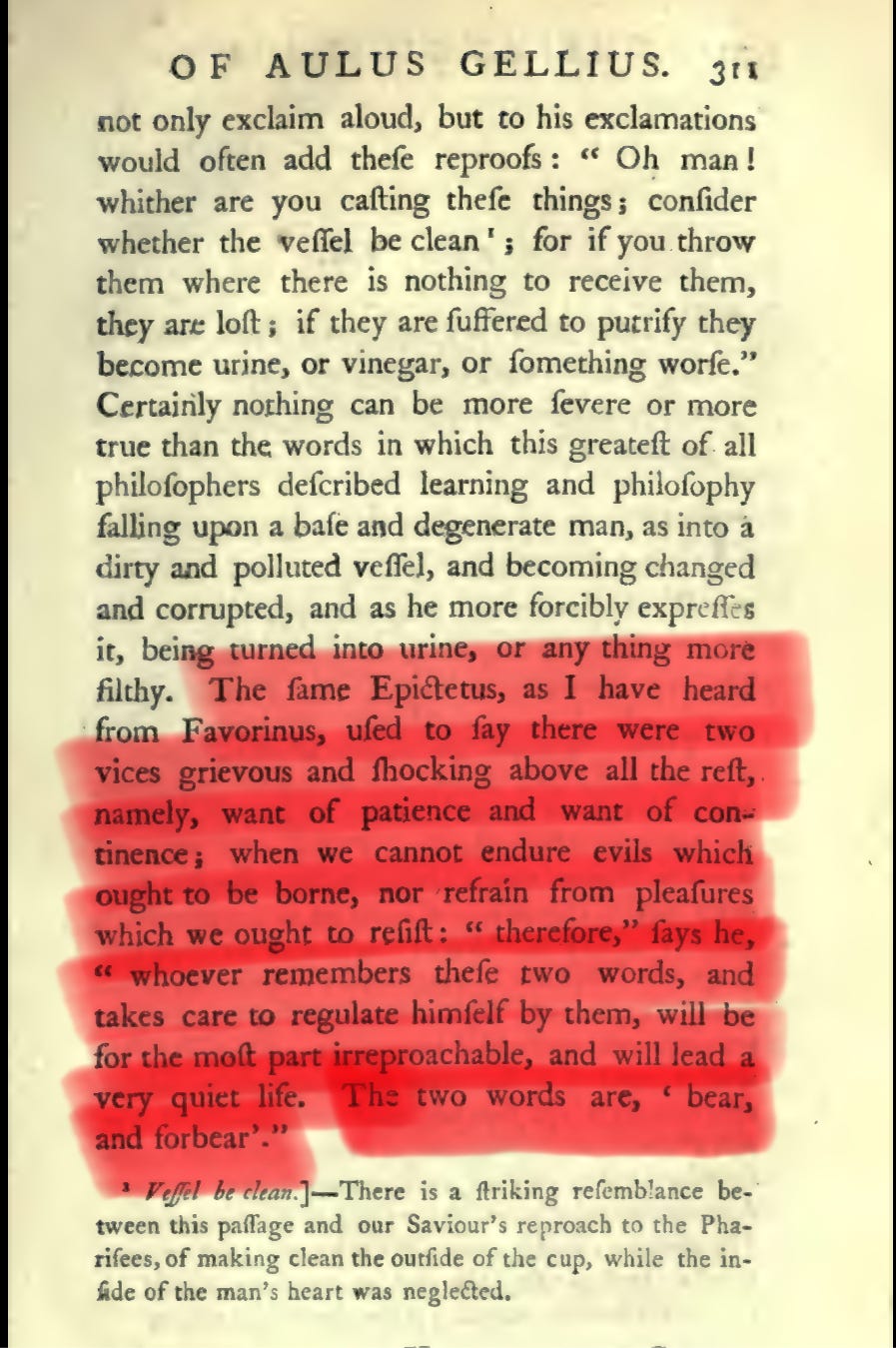

Epictetus’ idea that you should “bear what you ought to, and forbear what you ought not to” is a compact summary of his ethics of endurance and restraint, two of the core Stoic disciplines.

“Bear what you ought to” → Endurance in the face of the unavoidable

Bearing refers to patiently enduring whatever is not up to you but is in accord with nature or fate—illness, hardship, loss, death, insult, political turmoil.

Epictetus consistently taught that the wise person accepts such events without complaint, because resisting them only leads to misery.

To “bear” here means to stand firm, not give in to self-pity, and keep acting in line with virtue even when the world is harsh.

“Forbear what you ought not to” → Restraint from harmful or base action

Forbearing means refraining from doing, saying, or indulging in things that go against reason or virtue—whether that’s retaliation, overindulgence, cruelty, deceit, or giving in to irrational impulses.

In Stoic terms, this is about moral self-control—choosing not to act on desires or fears that would lead to vice.

Forbearance is the flip side of endurance: one is about how you respond to what’s done to you, the other about how you choose to act toward others.

Why both matter together

Epictetus is essentially saying:

Life throws at you things not up to you → you must bear them with fortitude.

Life tempts you toward things that are up to you but shouldn’t do → you must forbear them with integrity.

This maps neatly onto two of the Stoic disciplines:

Discipline of Desire/Aversion → bear the inevitable.

Discipline of Action → forbear the wrong.

Some contemporary examples

Here are three modern-life examples showing how Epictetus’ “bear what you ought to, and forbear what you ought not to” works in practice:

1. Workplace stress

Bear: You’re given an unrealistic deadline because of decisions made far above your pay grade. You can’t change the situation, so you focus on doing your best without letting resentment corrode you.

Forbear: You resist the urge to spread gossip or undermine your manager behind their back, even though it might feel good in the moment.

2. Illness in the family

Bear: A parent’s health declines with age. You can’t stop the illness, but you accept reality without denial and show up for them with patience.

Forbear: You avoid taking out your frustration on siblings or medical staff when things don’t go your way.

3. Public criticism

Bear: Someone insults you on social media. You can’t control their opinion, so you don’t let it disturb your peace.

Forbear: You resist firing back with a cruel reply, recognising that stooping to their level would compromise your character.

Reader Question

Epictetus implies we should ‘bear what we ought to and forbear what we ought not to.’ But in real life, how do I know which is which? How do I tell when I should endure something versus when I should refuse to go along with it?”

Tip / Donation/ Appreciation

We are all living in a cost-of-living crisis, and I find Substack’s paid scheme too much of a hassle. If you feel inclined to throw cash appreciatiojn my way, you can buy me a block of chocolate through my Kofi link here.

Great take, really. Bearing is about what happens to you, forbearing is about what you choose to do — and most of us tilt too far to one side. Some of us swallow hardship but vent it later, others stay composed but crumble when fate hits hard.

📌 Wisdom is learning to do both without letting one undo the other.

⬖ Practicing that double discipline at Frequency of Reason: bit.ly/4jTVv69